Solving Energy Waste with Human-Centered Design

Research, Development and Implementation of a Building Systems Strategies

2015 Case Study

Challenge

How might we reduce the carbon footprint of chain of corner stores in Veracruz (Mexico) with low-to-no-cost strategies?

How might we reduce the carbon footprint of chain of corner stores in Veracruz (Mexico) with low-to-no-cost strategies?

Scope

Deep dive research, energy audit, prototype (pilot store), complete implementation for brewing company GRUPO MODELO

Deep dive research, energy audit, prototype (pilot store), complete implementation for brewing company GRUPO MODELO

Outcome

Design and implementation of building systems solutions that lowered energy use by 25% in a chain of over 100 convenient stores

Design and implementation of building systems solutions that lowered energy use by 25% in a chain of over 100 convenient stores

Team

Benjamin Leclair, Human-Factors & Design

Marcel Brülisauer, Energy Science

Benjamin Leclair, Human-Factors & Design

Marcel Brülisauer, Energy Science

In the fall of 2015, I had just embarked on a new project as a design consultant together with a colleague specializing in low-energy buildings. Our CHALLENGE was to find ways to reduce the energy use for a chain of over 100 convenience stores owned and by Corona in Veracruz, Mexico. Borrowing methods from different fields to generate insights, ideate interventions and implement a clearly defined design strategy, we developed a series of low-to-no-cost interventions that lowered the store’s carbon footprint by roughly one quarter.

We defined a project schedule where we’d use one week to conduct desk-based research and plan out the project, followed by multiple weeks in the field to collect primary data and test out prototypes, with the final few days compiling a report from the Los Angeles office. Because we could speak only a bit of Spanish, learning from observation came naturally. We knew that we couldn’t look at each of the stores individually, so we worked with the client to select a location that offered a representative model in terms of design, sales volume, building typology and energy use. That would become our case study and pilot store. We spent a few days looking at the extremes; stores that used significantly more or significantly less energy than any other, but it wouldn’t have been particularly productive to focus on the exception for a project like this one. These stores generally performed differently based on three indicators: sales volume, building types and poorly installed equipment. As for performance, of course cooling down more beer requires more energy. And it didn’t take long to figure out that convenience stores built through retrofitting old houses would be less energy performant than new buildings, or that ice machines dating from the 1990s that never had their door gasket replaced would leak cold air and need more energy.

To begin, we wanted to understand how energy moves inside the store. We connected some homemade sensors to create an ENERGY AUDIT that would give us hard data on energy uses for every electrical device (AC, freezers, lighting, etc.). Collecting this baseline information was not only critical to seeing the big picture, but also necessary to calculate the effectiveness of the different design experiments that we planned to conduct later on. That would become our control data. We also conducted a DESIGN ETHNOGRAPHY of the store. While the sensors did their work, we hung around the shop, helped the staff where we could, observed and eventually rigged prototypes. We took notes on everything and nothing. On how the team propped the doors open to receive dry deliveries; how staff members readjusted the AC temperature throughout the day; how they used their downtime; we looked at customers buying and popping popcorn bags in the store’s microwave, etc. Part of me wanted to get a bag of popcorn of my own, and part of me wanted to prop the door open to let the smell of cinema butter get out. It took self-control to resist doing either, not because intervening would have compromised the data (this is participant observation after all), but rather because I wanted to see how long it would take for anyone else to break!

We also conducted some SPATIAL ANALYSIS to understand the logic behind the hundreds of micro design decisions taken in building the store. Why build a store with wide (and costly) windows if you’re going to block them with floor to ceiling bags of chips? Why use reflective paint on certain walls but not others. Why keep the lights inside the fridge turned on overnight? We defined these architectural and system design questions through observations, but generally found answers by asking. Not everything is behavioral after all.

After observing, measuring, analyzing and having short discussions with staff and clients, we ideated over a dozen design interventions to test out. Some of these PROTOTYPES were based on our ethnographic observations, others on the energy audit, and a few were conceived as ACTION RESEARCH projects. This refers to a technique where you design something new to analyze how people respond to this new ‘actor’. While it’s entirely possible that the things we introduce through action research bring value, the purpose is to study human responses to a prop rather than test out the usability/worthiness of that prop.

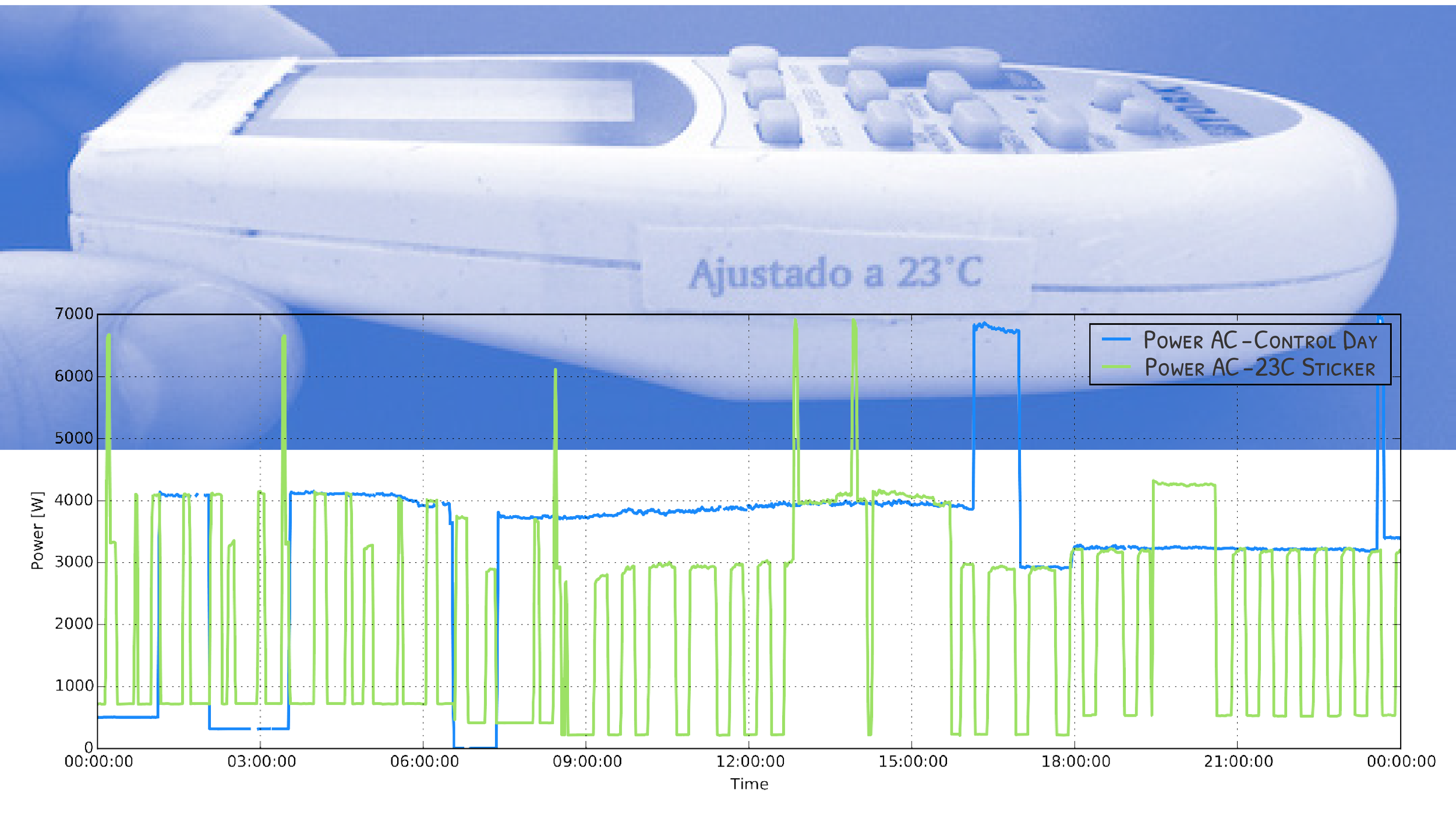

Our interventions ranged from changing the temperature settings of ice machines, to repainting the building’s roof from terracotta to white (see image on p.14), to rigging plastic flaps on a food refrigerator, to making homemade stickers for the AC remote that asked for the temperature to be set to a certain degree. We implemented each of our PROTOTYPES one-by-one so that we could measure their individual impact on energy use (quantitatively) and on people (ethnographically). What we wanted to know was fairly simple: whether the strategy would lower the carbon footprint, and how it would impact the staff and customers’ experience of the store. Because the sensors measured how each device was being used whether we were inside the store or not, we were able to assess if our presence in the store changed the way people used the equipment.

One of our cheapest prototypes was the remote-control stickers (see image ). It was also one of the most impactful! Prior to applying the stickers, employees re-adjusted the temperature throughout the day constantly. If you’ve ever shared an office where you can control the thermostat, you know exactly the kind of micro tensions that this can cause. One employee in particular loved it really cold. Like 18ºC (64ºF) cold. Moving from that kind of temperature to the outdoors is physically tiring for most. One manager wore her Corona parka, provided to restock the cold room (proudly kept just below freezing), while she worked the cash register. This is Veracruz, Mexico where the average highs in December hover around 27ºC (80ºF). That really wasn’t just a carbon footprint problem, but a workplace comfort problem.

After testing different temperatures in situ, we settled on 23ºC (74ºF). It was refreshing enough to draw clients in and warm enough for employees to dress normally. Sure, some people would have ideally liked it a little cooler or warmer, but 23ºC was the communal sweet spot. We could have used our insights to define a more advanced type of intervention, like creating a system to control all store temperatures remotely from the headquarters (a technology we recommended for future stores), but the stickers worked just fine. They cost close to nothing and left employees with some level of autonomy rather than taking away the AC remote, a strategy that would have been demeaning and patronizing. A little guidance and direction was all that was missing.